The Camelopard:When The Giraffe Came to the Staffordshire Potteries

In the fast paced world of the 21st century, there can be few areas of modern life which remain immune from the whims of fashion; manufacturers react swiftly to meet popular demand for goods which reflect the newest craze. The latest creation has barely left the designer's atelier before fashionistas are poised to declare it yesterday’s look. Even while attention centers around the most recent event or celebrity or style, the public gaze is constantly seeking out the next new thing.

Past centuries had proved no less fickle, constantly receptive to diversion by the new and exotic. Then, as now, design and style responded swiftly to reflect events, from historically heroic figures, military triumphs and disasters (although rather fewer of those and commonly only as represented from the victorious side!) to less tangible but more fantastical tales of magical creatures.

The dragon appears frequently in ancient and medieval art and literature, strange and mysterious creatures were believed to exist in far-off lands and in dark, secret places upon the earth: unicorns griffins and other fabulous animals were depicted in lavishly illustrated bestiaries of the middle ages. How much more wondrous, then, for these beliefs to be confirmed in tantalizingly unexpected ways when tales of real exotic beasts filtered back into 18th and 19thc Europe. The invention of the printing press allowed wider distribution among the general populace, affording greater access to scenes depicting these marvels, engraved from drawings and paintings based on the first-hand accounts of returning travelers - adventurers or soldiers.

The potteries were no less responsive to changes in taste, creating and adapting their designs to capitalize on prevailing market demand. Josiah Spode introduced the first in the Indian Sporting series in 1809, the copper plates engraved for the transferware were drawn from Samuel Howitt's illustrations published monthly in Oriental Field Sports, Wild Sports of the East, with accounts written by Captain Thomas Williamson. The multi-scene prints, from which the Spode pieces drew their source, featured elephants, tigers, bears and even hogs and wolves from the Indian sub-continent. Extraordinarily foreign and exciting enough for an emerging middle-class market, ready and eager to be both entertained and to visibly demonstrate their own taste and growing prosperity.

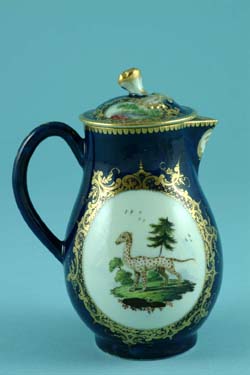

And so it was on the first appearance of the giraffe into Europe in the early 19thc, after a gap of more than 300 years. This wondrous creature from the African continent was not unheard of at that time although, judging by the few strange portrayals on the ceramics, its precise form must surely have long faded from collective memory.

From surviving temple decoration, it is evident that the giraffe was familiar to the ancient Egyptians, but there is no record of it in Europe until a single giraffe, captured in North Africa, was included in Julius Caesar's triumphal procession into Rome in 46 B.C. Following the Gallic Wars and Caesar's victory over Vercingetorix, the chieftain also formed part of the procession, albeit as a wretched trophy. The spectacle must have provided a vivid contrast between the lofty, graceful giraffeand the miserable prisoner: both aliens and captives but the chieftain destined to meet an earlier, more certain and grisly end. Giraffes continued to be seen in Rome over the next few centuries and Pliny the Elder, in his Historia Naturalis of 1ct century AD, refers to the giraffe, as 'a beast that has the neck of a horse, feet and legs like an ox, and the head of a camel. It is a reddish color and has white spots, so it is also called camelopard.' It is evident they proved to be poor value in the arena, providing little sport, for Pliny also observes, 'From this it has subsequently been recognized to be more remarkable for appearance than for ferocity, and consequently it has also got the name of wild sheep.' Perhaps for this reason, thereafter they seem to have vanished from Europe for another millennium, until a brief reappearance in Italy at the Medici court in the 16th century.

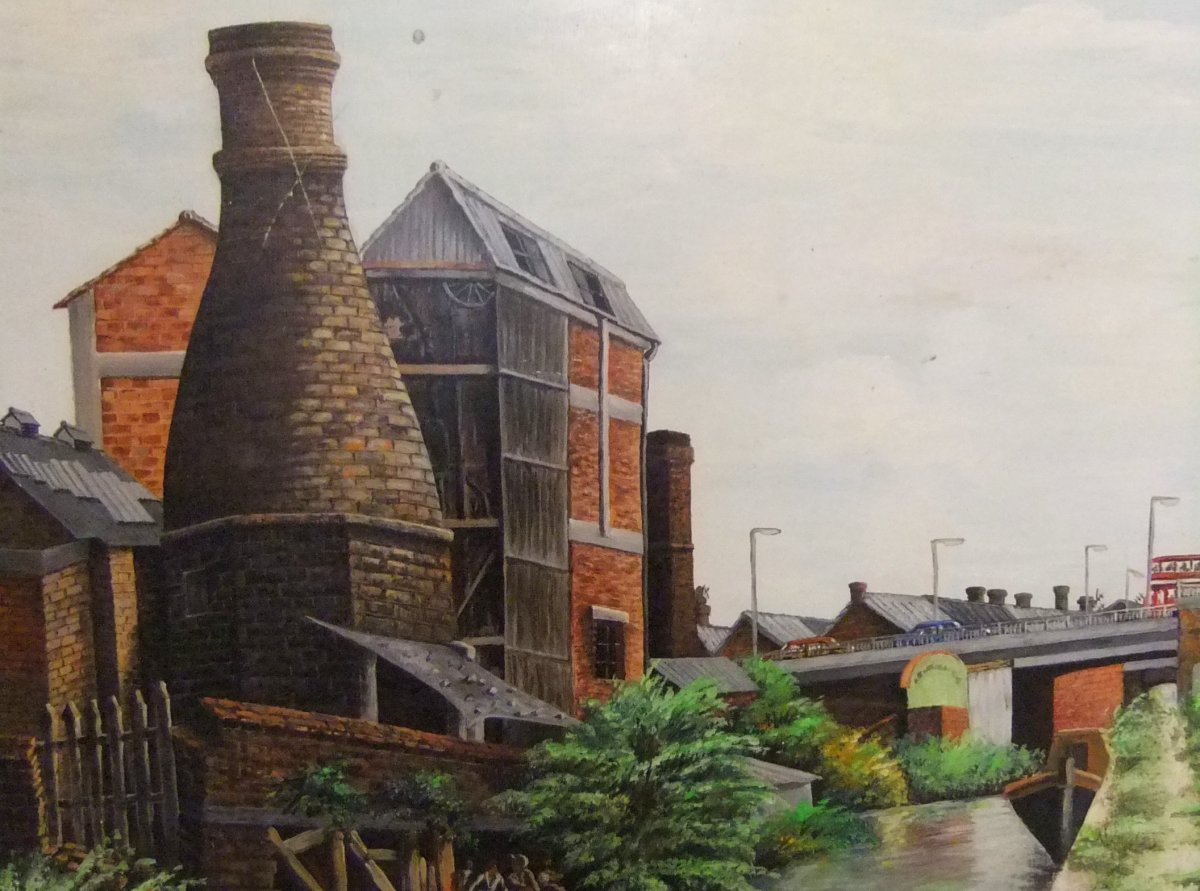

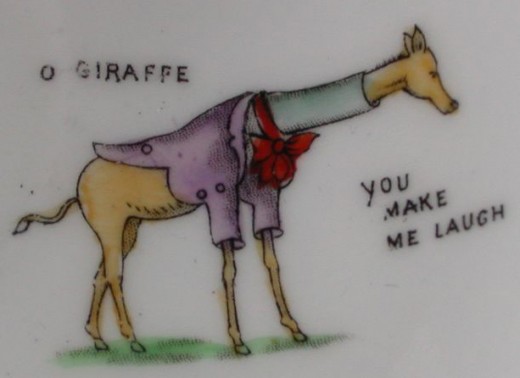

From the sporadic depiction of the camelopard on European ceramics, the animal evidently falls back almost into folklore, since little accurate recall of its true shape and form seems to have been retained. When the camelopard does make a rare appearance, its portrayal shows an almost literal interpretation of its name. The Worcester porcelain jug is superbly painted by the Irish miniaturist Jefferyes Hamett O'Neale but the giraffe itself inevitably brings more to mind an ancient dragon than the elegant creature we would recognize today.

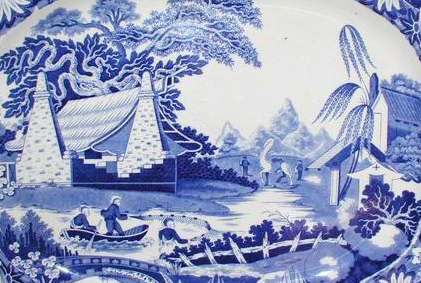

Even more fantastical is the peculiar creature, distantly viewed on the path in the middle distance, on this scene from an earlier plate produced sometime before 1810. Here, the camelopard resembles a hybrid, not so much between a leopard and a camel, but perhaps a misalliance between a llama and camel. The quirkiness of this scene is further enhanced by the curious choice of what appears to be a Chinese landscape. Whatever its origin, the print maker appears to have drawn largely from his own imagination and, if not zoologically accurate, the print is all the more charming as a result.

Intended as a diplomatic inducement for military aid in putting down an insurrection in Greece or, at the very least, to avert French intervention in Athens, the wily Viceroy of Egypt, on receiving the gift of three giraffes from a local governor, sent them on to be presented to each of the heads of Austria, England and France, considered at the time to be the three most powerful nations in Western Europe. Two of the giraffes were siblings and upon arrival in Cairo in 1827, the French and English consuls drew lots with, as later events transpired, the French winning by far the better draw, for not only did it cause a sensation on its entry into France, it survived longer than the sad fate met by the giraffe that travelled to London. Both the Austrian and English animals suffered early and untimely ends, the former succumbing within a year to disease in its legs and the London giraffe, similarly afflicted, fading into weakness and dying quietly barely two years later in 1829. But for those short periods, their presence was a cause célèbre in both capitals.

Ultimately his diplomatic ploy availed the Viceroy little and the French were signatories to a joint treaty opposing both Muhammed Ali and the Ottoman Empire even before Zarafa had made her first appearance at St Cloud.

The healthy female giraffe that was destined for France travelled by ship with every comfort, allocated her own cabin steward in the form of a groom from the French Consulate, assisted by native keepers from the Sudan, all of them charged with attending to her every whim. Three cows accompanied her on her voyage to supply her daily six gallons of milk and she arrived in the port of Marseilles in healthy and thriving condition. Her keepers unfailingly indulged her every caprice and, upon noting how the fashionable 'mademoiselle' spurned plain water, a menu was devised to suit her appetite, which was observed to favour milk and barley. After overwintering in the port, to rest and acclimatize to her new surroundings, it was decided that the next leg of her journey to Paris would be on foot and, after lengthy preparations, the cavalcade set out. At every step of her 500 mile route, crowds poured out to witness this marvel from Africa - giraffmania swept the country. Manufacturers raced to produce wares to feed the insatiable public appetite for giraffe-themed goods, producing her image on everything from fabric, china and even wallpaper!

The enthusiasm of the Paris crowds was matched by those in London and Vienna for their own specimens but, although the giraffe hysteria in the London and Vienna came to an abrupt end with the untimely demises of their animals, the French giraffe might be considered ultimately to have been the more unfortunate, since she lived long enough to witness the fickleness of public favour, when Paris was diverted by a new fancy with the arrival of a Red Indian family. Although the giraffe remained safely and even luxuriously housed in the Grande Rotonde, she received fewer visitors after her fall from fashion, lingering on, lonely and unloved by fashionable society, in near solitude until her death, still a mademoiselle, in 1845. Her corpse was stuffed and sent to the museum at La Rochelle where, some 160 years after her death, she now renews her ability to cause surprise and wonder, when the unsuspecting visitor rounds the stairway and encounter Zarafa peering impassively down from the half-landing.

But this sad fall from popularity was yet to come and in 1829, after the death of the English giraffe, there existed the unpalatable situation whereby the French king had a Giraffe and the English King did not. Such a situation was not to be borne and, after several failed attempts to procure a replacement, the Zoological Society's commission of M. Thibaut, a French trader in the Sudan, finally bore fruit and four giraffes landed at the docks in London on the morning of 1836.

The new London arrivals made their own procession, of shorter duration that had Zarafa from Marseilles to Paris. A stately three hour parade, escorted by M Thibaut and Nubian keepers in native dress, alongside a detachment from the Metropolitan Police, brought them safely to the Zoological Gardens that evening, where they settled immediately into the new elephant house, temporary lodgings until their own purpose built accommodation was completed the following year. Although not inspiring quite the unbridled mania as had been shown for the French giraffe, the adopted Londoners held the affection of the public who continued to visit the original four and their growing family,. The first recorded birth in captivity was to Zaida in 1839 and there were a total of seventeen births before 1881 when the last of the original Thibaut line died out.

It was the Thibaut giraffes which were the inspiration behind this Ridgway pottery transfer print based on George Scharf's engraving. The Ridgway engraving C1836 varies from the original source, the transfer print depicting only the central trio of giraffes but essentially in identical pose, and removal of one figure group with small changes to the arrangement of the figures to the right.

Little is new under the sun. For the 2011 Spring collection, Louis Vuittion's models paced the fashion catwalks in giraffe themed sandals and suits but, from the arrival of Zarafa and Zaida in London and Paris in those heady days of the 19th century, Giraffa camelopardalis has remained an enduring them in pottery and porcelain, beloved by children and adult alike.

Giraffe Themed links

- Camelopardalis

The Giraffe in the Night Sky! - Worcester Porcelain Museum

The Worcester Porcelain Museum cares for and displays Worcester porcelain, factory archives, pattern, design and employment records. Period settings and an audio tour provide access to and encourage study and enjoyment of the worlds' largest collecti - http://www.flickr.com/photos/theudric/5152115591/

The Giraffe on the Stair: Zarafa at La Rochelle - Find more giraffe-themed items on Ruby Lane

Shop for Giraffe on Ruby Lane, a marketplace to buy and sell quality antiques, collectibles and artisan jewelry from thousands of vetted sellers since 1998.

Further reading:

'Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris' - Michael Allin

'The Ark in the Park' - Wilfrid Blunt